Electric Cars 101: Answers to All Your EV Questions

What you need to know to decide whether going electric is right for you

Electric vehicles (EVs) are becoming increasingly common, with every major automaker introducing at least one model. Even as tax credits disappear in the U.S., the worldwide trend toward electrification continues. But is an EV right for you? The experts at CR are here to help you decide.

Which Models and Types Are Available?

Electric vehicles come in all shapes and sizes, from small hatchbacks to luxury SUVs. Some are electric versions of familiar models, such as the Ford F-150 Lightning pickup truck. Others, such as the Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Kia EV6, are all-new vehicles designed to be electric from the very beginning.

There are currently more than 150 EV models on the market—a massive increase from 2020, when there were just 6 models. While some early EVs could drive only 80 or 90 miles on a charge, many of today’s models get more than 250 miles.

Read about all of the pure electric models (BEVs) that are due to arrive soon, and check our full ratings of EVs we have already tested.

Shopping for an Electrified Car or SUV?

See our hybrid/EV ratings and buying guide.

Photo: Tesla Photo: Tesla

What Does an EV Cost to Buy?

Many EVs are in the $40,000 to $55,000 range. Only the Nissan Leaf starts under $30,000, while high-end models from BMW, Lucid, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Tesla extend into six figures. A CR analysis of sales data shows that the average new EV sells for around $60,000—about $10,000 more than the average gas or hybrid car.

In the years ahead, it is expected that EVs will gain price parity with similar gasoline models, as battery and production costs come down. It may be worth the wait if you’re looking to save money.

Photo: Chevrolet Photo: Chevrolet

What Does an EV Cost to Own?

Battery electric vehicles have fewer components than a plug-in hybrid or an internal combustion engine vehicle, so they often have lower maintenance costs because they don’t require fluid changes or tuneups. An analysis of EVs by CR found that EVs generally cost less to own over a typical ownership period than their equivalent gasoline-powered counterparts—although a less-reliable EV may end up needing pricey repairs, so be sure to choose a vehicle that scores highly on CR’s reliability ratings.

The cost of the electricity to charge an EV is almost always hundreds of dollars less per year than the fuel expense for a similar gas-powered vehicle. However, depending on where you live, how much you pay for electricity, and what kind of vehicle you’re shopping for, it may take many years—if ever—for those savings to make up the difference between the purchase price of an EV and a similar hybrid vehicle. Our analysis shows that luxury vehicles and trucks tend to have a quicker payoff than smaller EVs.

Figuring out an EV’s energy costs is a lot more complex than doing the same for a gas-powered car, but the Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center has an easy-to-use calculator at afdc.energy.gov/calc. Check out any local incentives that might make it cheaper to charge an EV at home overnight. You can also calculate how much you’ll save if your home has solar power.

Can You Get a Tax Break on a New or Used EV?

While the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) offered tax credits of up to $7,500 on new EVs and up to $4,000 on used EVs, new legislation means those federal credits do not apply to cars purchased or leased after Sept. 30, 2025.

Your state or even your local utility company may have additional incentives or discounts, however, and there could be state or local incentives that can significantly reduce the cost of installing a charger at home.

Should You Lease or Buy an EV?

If you’re considering an electric vehicle, you should think about leasing instead of buying. Although the market for EVs is changing rapidly and unpredictably, leasing offers some advantages.

Because you lease for only a few years, you won’t be stuck with a car that has outdated battery technology or charging standards, because these are still rapidly evolving. And if an automaker drops the price of a new EV by thousands of dollars overnight—as Ford recently did on the F-150 Lightning—you won’t take the hit if your leased vehicle is suddenly worth less than it was the day before.

Photo: Audi Photo: Audi

Where Will You Charge It?

Chances are, you’ll do the majority of your charging at home. In a fall 2022 Consumer Reports nationally representative survey of 943 Americans who say they own or lease EVs, we asked them to estimate what percentage of their charging happens at different locations on a typical week. On average, those who do any charging at home say that 64% of their charging happens at home; those who do any charging at public chargers do 31% of their charging there; and those who plug in at work at all do 30% of their charging there.

If you plan on charging at home, that usually means you’ll need ready access to a 240-volt EV charger. These are available online through Amazon, Costco, Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Sam’s Club, among others, and we’ve tested the most popular models. The cost is typically $500 to $700. Unless you are pushing the range limit on a daily basis, you won’t have to fill up your EV from empty all the way to full very often.

You’ll need a professional electrician to install a Level 2 charger. An installation entails putting a special 240-volt receptacle, like the ones used for a clothes dryer, in your garage or near your driveway. You can also hardwire a charger, which may allow for quicker charging. Expect to pay about $500 to $1,200 for the work, plus $500 to $700 for the wall-mounted charging unit. Of course, costs will vary depending on your specific setup. Installing a charger in an older home that needs a wiring upgrade could cost thousands.

If you don’t have a garage, don’t worry: Nearly all chargers are weatherproof and waterproof and are designed to safely be installed outdoors. But if you don’t own your own home and can’t get permission to install a charger in your rental, or if you don’t have off-street parking at all, you may be unable to install a charging station.

A few EVs, including the Ford F-150 Lightning, Genesis GV60, Hyundai Ioniq 5, Kia EV6, and Rivian R1T, have built-in plugs that can provide short-term electric power for smaller household goods and appliances.

What About Public EV Chargers?

Although there are now more than 53,000 U.S. public charging locations, most of them are Level 2 chargers—the same kind you’d have installed at home—and take many hours to fully charge a battery (more on that below).

If you’re on a long road trip, you’ll most likely want to charge at publicly accessible DC fast chargers. These are becoming more common, even if they aren’t as ubiquitous or easy to use as gas stations. Most of them are available off major highways or at rest areas.

How easy they are to use can often depend on what kind of vehicle you drive and brand of charger you’re trying to use. Tesla owners have access to a wide network of Tesla Supercharger charging stations, and we have found that they make topping up a Tesla seamless, convenient, and relatively quick. Owners of other EVs rely on a patchwork of chargers that aren’t always convenient to access, might not always charge rapidly, and usually require the user to fumble through an app or swipe a credit card to activate the charger.

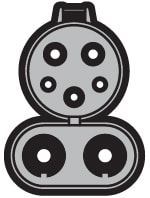

Many new vehicles are compatible with some Tesla Superchargers, whether through a built-in NACS plug or an adapter. We’re keeping a close eye on this development. Nissan Leaf owners will have to search for a fast charger with a specific kind of plug, called CHAdeMO, which isn’t used by any other new pure EV sold in the U.S.

Plugging in a vehicle can require more physical effort than gassing up a car, too, especially if you have to drag a heavy cord to reach the car’s charging port. There are no “full serve” charging stations, and because EVs have their charging ports installed in various places on the vehicle, not all chargers are conveniently set up for a charging cord to reach the outlet.

Before you go on a trip, download apps that can help, such as those from the ChargePoint and Electrify America charging networks. PlugShare is helpful for locating public chargers, too. Some vehicles have charging station data built into their navigation systems and can send you on a route that includes fast chargers. A Better Route Planner is a great smartphone app alternative that will help you plan trips with included charge stops. Always have a backup plan in case a charger isn’t working or takes longer to charge than you expect.

How Long Does It Take to Charge an EV?

If you charge at home, a typical 240-volt, 32-amp (Level 2) charger takes between 9 and 13 hours to fully charge an EV that can go more than 200 miles—about 25 to 30 miles of charge for every hour your vehicle is plugged in. A public Level 2 charger charges at the same rate but is appropriate for cases where people might spend a few hours at a restaurant or library or when parked at a train station, taking advantage of the opportunity to top off.

Things get a lot more complex with DC fast chargers, which can typically charge a battery from 20 percent to 80 percent in about a half-hour, on average. Tesla’s Superchargers are even quicker, with the speed varying by model, although many of them are open only to Tesla vehicles. Exactly how fast your EV charges depends on the size of the battery, how fast the car is able to take the charge, the amperage of the circuit, and even the weather.

In theory, chargers that can deliver up to 150 kW of power can add up to 9 miles of range per minute for some vehicles. Chargers that deliver up to 350 kW of power can add about 20 miles of range per minute—but only if the car has a compatible plug and is designed to accept ultra-fast charging.

In other words, if you drive a Ford Mach-E, Kia Niro EV, or Chevrolet Bolt—none of which is designed to accept ultra-fast charging—don’t bother searching for a 350-kW charger because your car can’t charge at that speed. Instead, the car will limit the flow of electricity based on the car’s max acceptance rate. For the example of the Mach-E, that’s 115 kW, which means a 150-kW charger would’ve been plenty. Although a Porsche Taycan or Hyundai Ioniq 5 can take advantage of the faster chargers, these stations can be harder to find—and in higher demand—than a 150-kW charger.

In addition, big vehicles with big batteries—like the GMC Hummer EV and Ford F-150 Lightning—take longer to charge, just as conventional trucks and SUVs with big fuel tanks take longer to fill.

In our own evaluations, we observed that EVs charge faster at DC charging stations when the battery is low and gradually ramp down the charging speed. We also noticed variations in charging speeds between different locations even within the same network, and that charging often took longer than manufacturers’ claims.

Photo: Kia Photo: Kia

What Is an Electric Vehicle Like to Drive?

We’ve found that most electric cars deliver instant power from a stop, and they are both smooth and quiet when underway, which is very gratifying. Even the most affordable modern EVs can post 0-to-60-mph times that would put a gas-powered muscle car to shame.

The driving experience can be quite different from a traditional gasoline-fueled car. There’s no transmission changing gears, and regenerative braking—which uses the car’s momentum as it slows down or coasts to create extra electricity—can start slowing down the car as soon as you take your foot off the accelerator. You can usually adjust how aggressively an EV accelerates or how quickly its regenerative brakes slow down the vehicle. Many offer what’s called “one-pedal driving,” where the driver can speed up or slow down just by modulating the accelerator pedal.

Despite their heavy batteries, EVs typically handle well because that battery is positioned low in the vehicle and there is no heavy engine over the front axle. Our testers often rave that many new EVs are very enjoyable to drive on our test track, even without the visceral thrum of a gas engine.

How Does Temperature Affect EV Range?

In cold weather, an EV’s range can drop dramatically because of the limitations of battery chemistry and unique power demands, such as managing battery and cabin temperatures. In our tests, we found that cold weather saps between 25 and 32 percent of range when cruising at 70 mph compared with the same conditions in mild weather and warm weather, respectively. Even with air conditioning on, we found that 80° F weather was optimal for battery range.

Before you drive, you can warm up your car while it’s still plugged in. That way, you won’t have to use valuable battery capacity to heat up the car’s interior, which would reduce range. Warming up your EV while it’s plugged in will also keep the battery warm, which makes it easier to accept a fast charge while on the road.

Can Roadside Assistance Help You if Your EV Runs Out of Charge?

An electric vehicle gives you plenty of warning before it runs out of range, so if you can’t make it to a charger, you’ll at least be able to safely pull over. If you find yourself in this jam, many roadside assistance services—including AAA and those offered by automakers and insurers—will tow you home (if it’s not too far) or to a charging station. They may even send a mobile charger out to you. Many new EVs come with at least a few months of roadside assistance. Check your car’s manual or the automaker’s website to see what is covered.

What About Hybrids and Plug-In Hybrids?

If a pure EV doesn’t fit your lifestyle but you still want to save money on fuel and reduce your use of fossil fuels, consider a hybrid or plug-in hybrid (PHEV) vehicle. Hybrid vehicles combine a battery pack, an electric motor that drives the car at low speeds, and a gas engine that kicks in for higher speeds, climbing hills, or recharging the battery. They offer significant fuel savings and lowered emissions compared with a gas-powered car, and they don’t ever need to be plugged in. However, they aren’t as efficient as a pure EV of a comparable size. (Learn more about hybrids here.)

PHEVs can operate on electric power alone for anywhere from 15 miles to 50 miles. Once their battery power is depleted, plug-ins transition from running on mostly electricity to operating as regular hybrids and driving about as far as a regular car, and they can quickly refuel at any gas station. However, unless they are plugged in regularly, they may not be as efficient as a traditional hybrid. (Learn more about PHEVs here.)

Electric Cars 101

Electric cars are bringing some of the biggest changes the auto industry has seen in years. On the “Consumer 101” TV show, Consumer Reports expert Jake Fisher explains to host Jack Rico why these vehicles might not be as newfangled as you think.