CR Tests Show Electric Car Range Can Fall Far Short of Claims

Temperature and other driving conditions have an impact; Tesla doesn't meet range claims year round

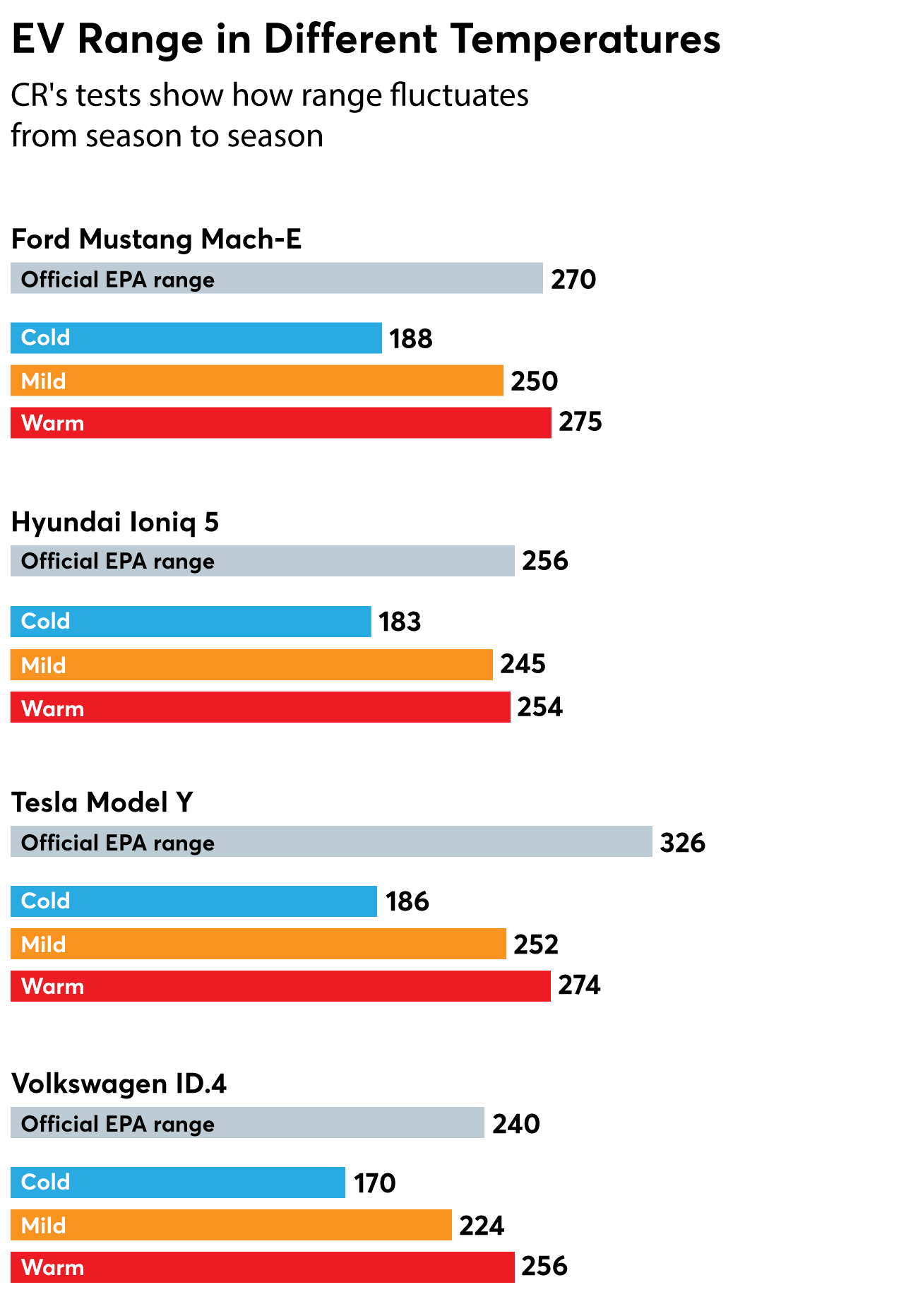

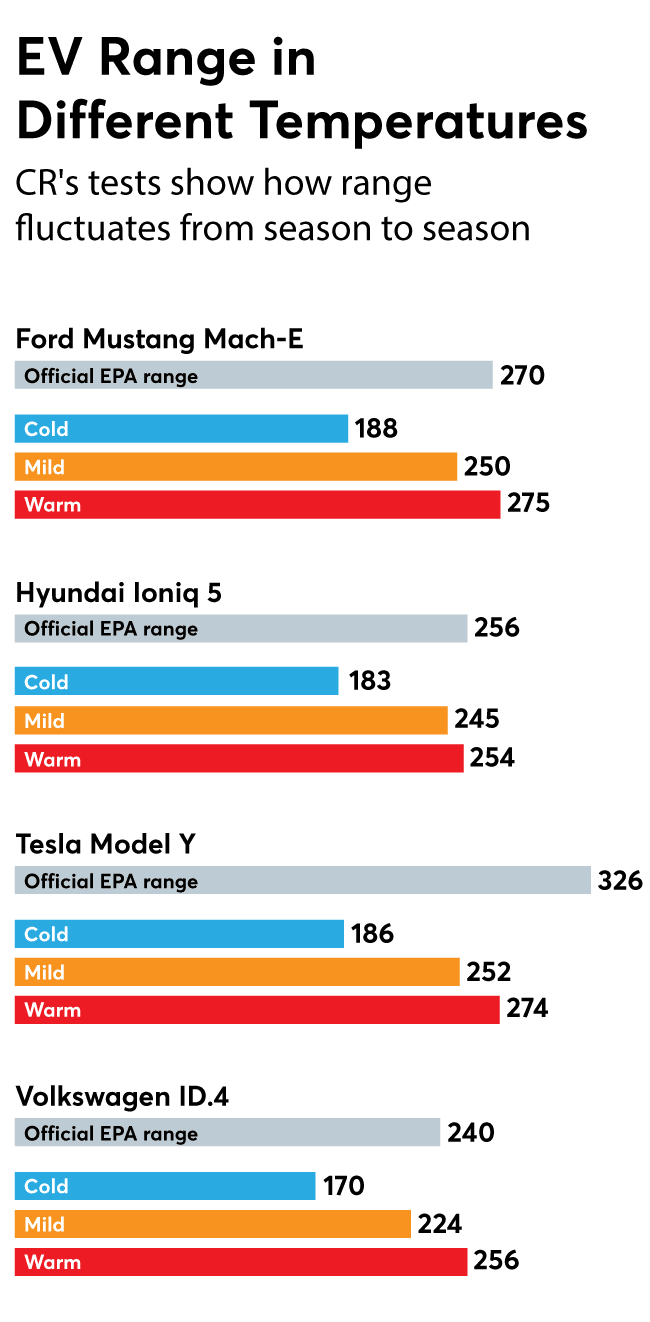

It’s well established that cold weather takes a toll on the range of electric vehicles. That’s because the cars must manage both battery and cabin temperatures, causing a significant drain. But by how much? And what about warm weather? Consumer Reports sought to answer these questions by conducting seasonal testing on popular new all-wheel-drive EVs: the Ford Mustang Mach-E extended range, Hyundai Ioniq 5, Tesla Model Y Long Range, and Volkswagen ID.4 Pro S. We found temperatures can have impact, but Tesla stands out for coming up short of claimed range no matter the weather.

Photo: Gabe Shenhar/Consumer Reports Photo: Gabe Shenhar/Consumer Reports

What We Found

This test series underscores the importance of taking range claims as general guides and being mindful of the “moving target” nature of EV range. Another difference between ICE (internal combustion engine) cars and EVs is that during constant cruising, an ICE car attains its best fuel economy. An EV, on the other hand, isn’t at its optimal efficiency when cruising on the highway, with limited opportunity to benefit from regenerative braking—energy that’s recouped from braking and coasting that gets directed back into the battery. Because the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) range is based on a mix of city and highway driving, the expectation for a test like this is that the vehicles will underperform their rated range at a constant highway speed.

We found a clear trend among these models showing that under different seasonal temperatures, winter cold results in the shortest range, followed by mild temperatures. It was on a typical summer day of sunny, humid, mid-80-degree weather that we saw the longest range, despite using air conditioning.

Other findings showed that the Mustang Mach-E stood out for having the most accurate range prediction—the indicated range used vs. the actual miles driven. Its real-world range also came within 1 or 2 miles of the Model Y on every run, even though the Model Y has a higher official EPA range. Note that the Mach-E has the largest battery of the bunch, at 88 kWh of usable capacity. The Ioniq 5’s cold-weather range ended up being only 3 miles short of the Model Y’s, which probably shouldn’t be a surprise because they have similar-sized batteries, but the Ioniq 5 is almost 200 pounds heavier than the Tesla. It’s interesting to note that the Model Y is the lightest vehicle of the quartet, differing by more than 500 pounds from the ID.4, which is the heaviest. Of the mild and warm runs we did with the Ioniq 5, it came the closest to its EPA rating. The Mach-E and ID.4 exceeded their EPA rating on the warm day.

How We Tested

We began testing in frigid February 2022, repeating the procedure in balmy April and in August heat. Originally, we tested only the trio from Ford, Tesla, and VW in the winter of 2022. We’ve since closed the loop and ran the Hyundai Ioniq 5 on a day that was 17° F (-8 Celsius) on the same route under the same conditions. Like the other three EVs, it followed the familiar trend, showing a remarkably similar 25 percent loss of range compared with the mild weather run.

The EVs were fully charged overnight before each of the runs and were allowed to precondition the cabin to 72° F while still plugged in outdoors. At the same time, we checked and verified the tire pressure. Heated and cooled seats weren’t used.

On the cold day, the temperature averaged 16° F (-8° C), meaning that considerable energy was needed to keep the cabin comfy and the battery pack in its ideal operating condition. The mild spring day was 65° F (18° C) during most of the drive, and the warm summer day was 85° F (29° C) during the drive. Each test day was clear and sunny.

The cars were taken on the road concurrently and driven on the same 142-mile round-trip route of Connecticut Route 2 and I-91. We used adaptive cruise control set to 70 mph and the widest gap to prevent any aerodynamic trailing effect or sudden decelerations and accelerations due to surrounding traffic. The regenerative braking mode was set to its lowest setting for each car to level the playing field. We paused for 10 minutes with the cars off at the midpoint.

Once back at our Auto Test Center, our engineers didn’t just record the remaining range indicated in the cars. They applied the ratio of miles of range used vs. miles driven throughout the trip to extrapolate what would be the total range for that specific trip. We also checked that ratio against the miles driven per each percent of state of charge (SOC) as extra validation of our methodology.

We intentionally didn’t drain the batteries until totally empty to reflect the typical owner experience. We don’t drive regular gasoline cars until they are bone dry, either.

Any EV driver or prospective buyer should also factor in the ease or difficulty of using DC-Fast charging on a long trip. Make sure you check out our DC-fast charging experiment.